Prior to the rise of compulsory schooling, it was common for young people to take on adult-level responsibilities at puberty. Indeed, in indigenous cultures, a rite of passage around puberty led to a transition to adulthood. Thomas Hine’s The Rise and Fall of the American Teenager documents just how common it was for teens in the US to take on significant responsibilities prior to the rise of compulsory high school. Ben Franklin, Thomas Edison, and Andrew Carnegie are among the many who began their working lives at puberty.

The terms “teen” and “adolescence” were created in the early 20th century. This wasn’t even a recognized category before then. John Taylor Gatto’s provocative thesis in The 7-Lesson Schoolteacher, that schooling trains us to be passive and dependent, is not even controversial for those who know much about the history of young people. Robert Epstein, former editor-in-chief of Psychology Today, wrote The Case Against Adolescence which makes the case that the infantilization of young people has been tremendously harmful. Human beings should take on significant responsibilities at puberty for healthy, normal development.

What Costs Might Be Attributed to the Prussian System?

I have made the case that schooling is a damaging evolutionary mismatch that is a causal factor in much of (most of?) adolescent dysfunction and mental illness. Does anyone believe that paleolithic teens, with young males and females eager to play an adult role in their tribes, exhibited the kinds of behaviors we see today? As behavioral health disorders (functional mental illness and substance abuse) surpass physical disorders as the largest causes of disability, it appears as though the opportunity cost of government schooling is quite high and getting higher. A 2024 study puts the annual cost of mental illness at $280 billion. A 2008 study puts the annual cost of substance abuse at $510 billion, which, with inflation alone, not assuming that the annual cost increased, would be $750 billion. Together we are at roughly $1 trillion.

Thomas Jefferson’s original vision for “public education” in the US consisted of tuition-financed local schooling with state subsidies for low-income students for three years. The cost of that would be a negligible fraction of our current $1 trillion annual education spending.

We don’t know how much of the $1 trillion in behavioral health costs would not exist if we had evolved healthier institutions, organizations, work, and other opportunities for young people, but if we take the evolutionary mismatch theory seriously along with Epstein’s The Case Against Adolescence, the amount is significant. We might be paying $1 trillion per year to cause $1 trillion in damage.

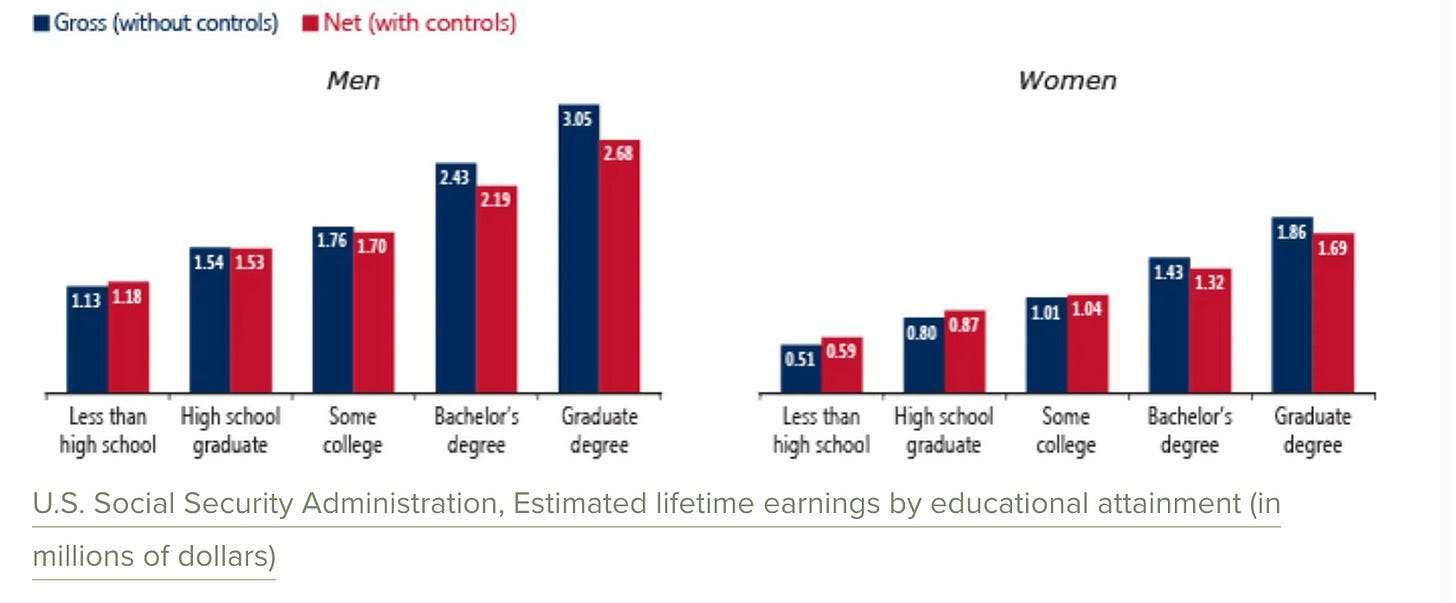

But doesn’t education add significant human capital? Evidence that more educated people earn more is solidly established:

This sort of evidence is usually taken as confirmation that governments should pay for education. Of course, the counterargument, as provided by economist Bryan Caplan, is that 80% of the wage premium for post-secondary education consists of signaling rather than human capital improvements. In addition, if one corrects for mathematical ability, the education premium drops by 40–50% for men and 30–40% for women. Jason Collins argues that if you control for math, reading, vocabulary, and “the kitchen sink,” it comes down to 50% generally. While there is no doubt some positive remainder for actual human capital development through education, it is likely a much smaller percentage of earnings increases than is represented in data as in the table above.

The reason why a Franklin, Carnegie, or Edison can be a leader without formal education is that people with sufficient motivation and ability can learn what they need to learn without schooling. The late Cole Summers (Kevin Cooper) showed that it is just as possible today (read his autobiography to the age of 14 to see how he learned without any schooling at all). Laura Deming, unschooled by her father, got into MIT at 14. Cliff Spradlin is a self-taught software developer who dropped out of high school and has been a software engineer at Tesla, SpaceX, and Waymo. Mikkel Thorup left school after middle school and has developed a highly successful business relocating expats. I’ve known hundreds of people with little formal schooling who have been highly successful in the 21st century. In careers open to merit, rather than credentialing, motivated people can learn what they need without formal education.

Ivan Illich became convinced in the 1970s that institutionalized education led to a loss of independence and initiative. Given that most of the value currently attributed to formal education is due to signaling, and that the human capital element (skills learned) can be learned without formal schooling (or with much less), then the net gains from formal schooling are much smaller than typically believed. Moreover, insofar as our counterfactual hypothesis for evaluating the opportunity costs of government schooling is NOT no schooling at all, but rather a voluntary market including home education, tutoring, private and religious schools, and apprenticeships, there would be abundant opportunities for acquiring the human capital component currently attributed to public schools. With the march of technology, from books to radio to films to TV to computers to the Internet to AI, skill development through some combination of human transmission, technological assistance, and personal initiative is easier than ever.

But what about the squashed entrepreneurial initiative from learning to be passive and dependent? And what about the anti-capitalist and victimhood ideologies taught in schools? And the negative habits many (most) students learn in public schools? Are the net outcomes from these characteristics more debilitating in a coerced K-12 system than the marginal value of human capital additions through government schooling over voluntary schooling?

While much harder to quantify, government schooling’s active efforts to undermine value creation while imposing the debilitating attitude of victimhood and developing bad habits surely have negative value. No parent (or vanishingly few) would choose schools or other learning experiences with these negative consequences in a voluntary educational system.

Separately, many of those who are not on the college track experience schooling as some combination of daily boredom and humiliation, some of which develops into the public-school-to-prison pipeline. A couple of studies have shown a dramatic difference in arrest and incarceration rates among those who went to private or charter schools rather than public schools. A voluntary, pluralistic system of education that did not damage young people in this way would save a significant amount of money, with roughly $100 billion annually being spent on incarceration (not to mention the damage to families).

Of course, these figures don’t include the tragedies of teen suicide, which increase about 30% during the school year, and the untold years of human misery from depression, anxiety, substance abuse, passivity, dependence, and victimhood rather than lives of agency, meaning, and purpose.

Let’s generously call the tradeoff between some human capital increase due to compulsory public education and the various harms it causes a wash, and leave the net cost at $1 trillion in direct costs and another $1 trillion in behavioral health costs annually due to compulsory public schooling.

When viewed in this light, compulsory public schooling doesn’t seem nearly as great as we are led to believe.